Musicians in the UK who know maker/repairer Paul Jefferies may have heard his critical opinion of modern commercial xylophones -- "They're not xylophones! They're piccolo marimbas!"

(You don't have to take my word for this as he has repeated the point on his blog.)

Which got me thinking about what it is that makes a xylophone a xylophone.

I'm not going to bore on about definitions and derivations (xylos + phonos -- yup, it's an idiophone of wood, let's move on) and I'm not bothered with the worldwide history of xylophone-type instruments ... In the 19th and early twentieth century a European folk instrument, no doubt with a rich prehistory of its own, was remodelled into a modern concert instrument. How and why did this happen? -- and what was seen as distinctive about this instrument? -- something that was worth introducing to (for want of a better term) art music.

In the 1830s the klezmer Joseph Gusikov wowed audiences in Western Europe with his "Instrument of wood and straw". Here they are together:

(Image from here).

Gusikov's instrument had tone bars (of fir, reportedly) laid across tightly wound bundles of straw -- Fanny Mendelssohn reports watching him put the instrument together in view of the audience before a concert. The bars were struck with spoon-like wooden mallets. It looks like a fairly standard example of the strohfiedel (German) or facimbalom (Hungarian) and presumably instruments of this type could be found throughout central and eastern Europe. It was referred to as the holzernes gelachter -- "wooden laughter" as early as 1511. In The Magic Flute Papageno's instrument is called in the original libretto "a machine like wooden laughter" (though Mozart, in the wings, played the music it purportedly made on a proto-celesta); at about the same time "laughter" was featured in another Viennese singspiel, Wenzel Muller's Sisters of Prague. So even before Gusikov, -- and long before its celebrated appearance in Saint-Saens Danse Macabre (1874) -- the instrument was known by the musical establishment and regarded as an effect that could be called upon if desired.

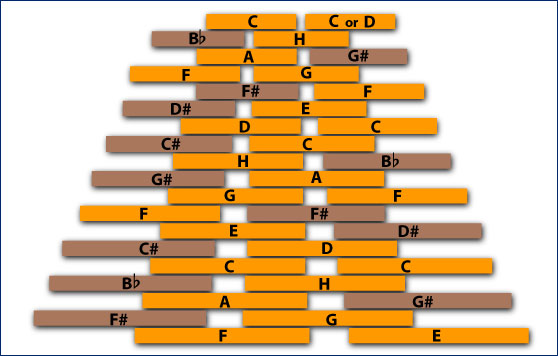

The examples with four rows of note bars, like Gusikov's, were fully chromatic. John H Beck or his contributor says "Generally the two center rows form a diatonic scale while the two outer rows contain accidentals, some of which are located on each outer row to enable the performer to play them with either hand." Which would be 1) a sensible way to construct such an instrument, and 2) a logical development from a notional one- or two-row diatonic layout. However at a first glance the instruments I've seen (in photos only, I'm afraid) don't seem to be arranged quite like that, but rather something like this:-

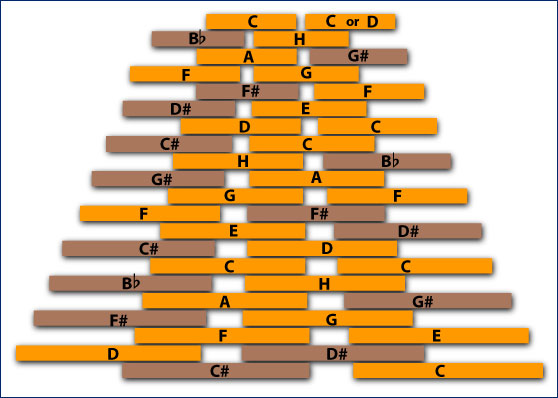

or, if you went for the pro version with extended compass:

I'm using H for B natural because we are in Europe, after all, and Bb for Bb because ... well we don't want any misunderstanding. The arrangement looks quite odd ... the chromatic scale goes snakewise up the ladders, with duplicate C and F, and each octave has a different configuration. But I'm guessing the additional Fs are there so that you can play a scale of C with alternate right and left sticks without crossing the hands. And the middle two rows provide a similarly straightforward G major scale -- so if you conceive of this instrument as being "in G" then Beck's description is sort of correct, if you count F natural as an accidental. The key of F is a pain, though, unless you swop the F/F sharp and H/Bb keys, in which case G is a pain. (By "pain" I mean "requires a more advanced technique").

If anyone out there is an accomplished strohfiedler, do tell us about this. Of course there may have been several competing keyboard layouts due to regional traditions, individual preference, etc.

The Gusikov-style instrument (let's just call it the strohfiedel from now on) was what Saint-Saens expected when he specified xilophone. And it is by no means obsolete. If you can stand to wear the Tyrolean uniform, there are career opportunities in the tourist trade:--

As you can see, the stroh (straw) has become purely conceptual. At some point in its history, the straw bundles gave way to cord passing through holes drilled in the tone bars. I would love to be able to give credit to someone for this development, which has been adopted universally by professional-quality tuned percussion, but I don't think it is known who first thought of this. Some village genius, or some smart but unsung instrument maker. If anyone has light to throw on this, please leave a comment.

One Albert Roth, in his xylophone tutor of 1886, proposed a two-row piano-style layout as an alternative to the cimbalom-style layout. According to Beck it was still assumed the player would stand at the bass end and reach over the instrument to hit the top notes, but presumably it was not long before players worked out that standing sidewise was preferable. Which would also mean that makers could now extend the range ad lib., or make the bars wider. The piano layout also makes adding resonators temptingly simple.

So between the 1870s and the early 1900s (when J C Deagan in Chicago started producing xylophones from a factory) a whole bundle of features that were typical of the folk heritage of the strohfiedel were amended. I intend to write a whole post on this question of the passage from folk music instrument to art music instrument, but for now will simply allege that the changes (which surely included regularizing the tuning) were in the direction of uniformity and reliability, allowing the performer to concentrate on the music as opposed to mastering the quirks of an instrument oversupplied with character and charm.

Coincidentally -- or ahem, NOT coincidentally -- the xylophone now began to appear regularly as a featured instrument in art music. Or maybe it just seems that way, because of its prominent cameo roles in pieces that are accepted as cornerstones of the 1900s repertoire; e.g. Strauss's Salome (1905), Janacek's Jenufa (1908), Stravinsky's Firebird (1910). And it was represented in recorded music virtually from the beginning, with cylinder recordings appearing as early as 1893, contributing to the widespread popularity of the xylo in vaudeville and light music (and home music-making), principally in the US. I can't say that Charles P Lowe (20-odd recordings before 1900), George Hamilton Green ("world's greatest xylophonist"), Harry Breuer ("Boy Wonder of the xylophone") or Teddy Brown are exactly household names, but even if forgotten (by some) they were characteristic celebrities of the modern musical world, somewhere between Paganini and Bert Weedon. In the 1920's the xylophone seemed on the point of being as ubiquitous as electric guitars in the 50s and 60s.

Strangely, this leap from obscurity into distinction happened before the xylophone was even a xylophone.

Which I will discuss in Part Two.